I’ve played through the Halo 3 campaign more times than I can count. First, there was the initial solo play-through. Then, it was straight to Legendary co-op. After that came the ‘LASO’ attempts, the achievement collection runs and the painstaking endurance test represented by the infamous ‘Vidmaster Challenge’. And yet, even after all of my jaunts down the Tsavo Highway or fights to stem the rising tide of the Flood, there existed one constant, one adherence that I would forever strive to abide by; saving the Marines.

Call it an implied responsibility, if you will. I am, after all, a seven-foot tall, 300 pound super soldier protected by the most technologically advanced power armour that human enterprise has ever created. And these Marines, for all of their heroism and valour, are little more than Covenant fodder at the best of times. This wasn’t a war that humanity could’ve ever won solely on the ground though, for if Earth was to survive the ensuing onslaught, then it needed a fighting chance. And who knows, maybe that very fighting chance came after I had destroyed the Wraith laying siege to our position, or when I gave Petty Sergeant Thompson a fully-loaded Spartan Laser in exchange for her half-empty Assault Rifle. In Halo 3, things were more straightforward. I was the focal point of the universe, guardian of the soldiers serving beside me, and bane of the Covenant’s quest to eradicate humanity. I was the man that UNSC Marines were relieved to see appear at their backs, and the spectre lambasted as a “demon” by those unfortunate enough to be on the wrong end of my rifle barrel. I was the hero of this story, and heroes always live on.

This is what you’re told to believe. This is the ingrained mantra of the original Halo trilogy. And, it’s also the basis of Halo Reach’s single biggest deception. “With all due respect sir, this war has enough dead heroes” says Cortana to Keyes at the beginning of Halo CE. Little did I know, she was talking about people like Noble Six. To understand why Halo Reach simply worked as a standalone chapter is to understand the ethos of games of its ilk. We’ve seen the themes of revenge, love, salvation, redemption and unity in equal measure. Heroes dying, heroes surviving, villains bowing out of proceedings with a certain stringent inevitability. Sometimes, this overpowering rigidity can blight even the most decadent of worlds.

At the very least though, you can always rely on hope. Hope, like my duty of ensuring the survival of the UNSC Marines that fought with me, is a constant. There was hope in Halo 3, a feeling that no matter how bad things got, humanity would survive and the earth would continue to spin on its axis. Every setback, every loss, did nothing but instil this will to fight even more, for when the end came, when the curtain finally dropped on the events of Halo 3, hope had ultimately prevailed. Halo 3 was a rousing chorus of victory and endurance. Halo Reach though, a swan song of desperation and defeat.

In Halo Reach, hope brought with it a cohort – hopelessness, a simple antonym that, by contrast, wrought and ruined Halo’s far more traditional emphasis on fighting through the storm. In Reach, that storm was just a little too fierce to navigate. It starts relatively slowly. The discovery of a few UNSC corpses here and there, a lone distress beacon sounding off in the distance, a power failure at a local communications hub. But after that first skirmish with the Covenant begins the snowballing effect that will eventually consume you. “The Covenant are on Reach” declares a specialist over the radio. And so begins the coming of the end.

Halo Reach paints its picture of hopelessness through a consistent, systematic dismantling of the opulent world around you, and through an unshakeable series of losses, each more devastating than the last. For every setback, there exists another plan of action, but for every plan of action, there exists another setback. Who can forget obliterating a Covenant shield garrison with a MAC blast from an in-orbit frigate, only to have the frigate assimilated by an unfathomably large Covenant supercarrier perched above it. Or taking the fight to space, only for it to cost the life of Reach’s most devout advocate, the loyalist Jorge, a Spartan who gave his life thinking he just saved the world, when in reality, he had merely affirmed its impending destruction.

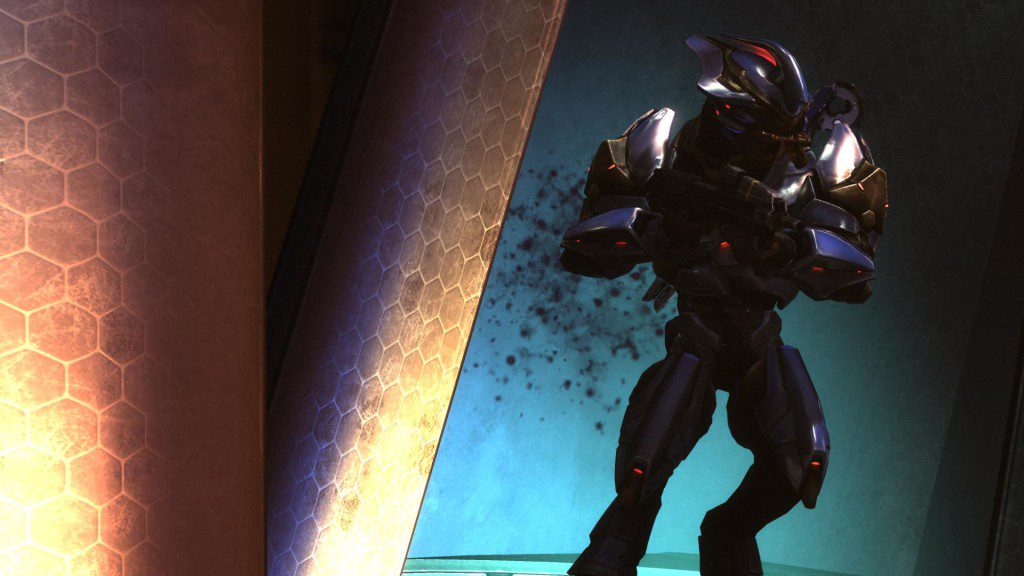

For as the ground erodes away at your feet, both literally and figuratively, so does the strength of your team begin to waver. Jorge, a Spartan of Reach, left to die in the cold vacuum of space, alone, frightened. Kat, the tactician, a calculated Spartan forever looking ahead, ambushed and eradicated during one momentary lapse. Next came Emile, the fighter, dying underneath a pile of Elite corpses that he had every intention of taking with him. And finally, Carter, the captain, symbolically going down with his ship. “Spartans never die” reads the creed. On Reach they do.

Another of the themes that punctuated Halo Reach’s darkened, harrowing tale was the lack of control you had over the planets fate. As Master Chief, there was always a knowing of what to do and how to do it, but as Noble Six, things weren’t nearly as clear, the spinning plates that you had to keep atop their poles eventually falling one by one. There’s one moment that stands out above all else when referring to the absence of control. After washing up alone in New Alexandria, you’re tasked with activating AA cannons to ensure that civilian transports are able to get off-planet alive. The skies are awash with pink and purple and bright yellow flak, and all you can do is tilt your head upwards and hope that the glowing green button you just pressed would be enough to defend the evacuees. But as the first shuttle frantically ascends before being given the all-clear, it is instantly cut in half by searing white plasma, you and all of your allied forces still shoreside having been given a box seat from which to ponder your collective helplessness.

But with a delectable sense of irony came the definitive act of Noble Six, an act that almost restored parity, this time having returned a semblance of control to the player. This of course, was the task of ascending to the anti-aircraft gun and ensuring that Keyes and Cortana made it to the Pillar of Autumn alive, something that would ultimately cost you your life. It’s here where Halo Reach’s epilogue is written, on the dusty, blood-ridden planes of a cavernous gorge soon to be vitrified by a Covenant glassing laser. Standing stoically and watching intently as the fleeing Pillar of Autumn becomes slowly enveloped by the bleeding sky, Noble Six is forsaken, his team dead, his hope all but extinguished. And yet, I still have control? I can still move? ‘SURVIVE’ reads the text emblazoned across the top of the screen. And for the first 15 minutes, I did. I expended my grenades, discharged all of my rockets and laid out several Elites with the stock of my Marksman Rifle. At some point though, between cracks appearing in my visor and the expulsion of the final round from my chamber, conceding was just the right choice to make.

From a technical point of view, the Reach finale was a masterful marriage of gameplay and narrative, but in terms of the story, it was even more impactful. Reach had died long before Six took that final telling sword lunge to the abdomen, and it had died long before the fall of New Alexandria. In reality, Reach had died during the least hectic moment of the game, the moment when Noble Team first made visual contact with the Covenant on that sodden farm deep in the highlands. Reach was simply never saveable now matter how hard you tried, with that being the games most telling admonition. Some wars you simply don’t win. Some heroes are forgotten. Some Spartans do fall. And so the Covenant marched on.

“Our victory, your victory, was so close. I wish you could’ve lived to see it.”