It was upon first ignoring the rattling of the pay-phones that the fictional New York at the heart of the original Grand Theft Auto began to look that much bigger. There was no horizon in this two-dimensional metropolis, but its labyrinthian streets and towering high-rises made the blip that represented your character feel all the more insignificant. Your choice here was a simple one – either answer the call and do what you were told, or let the phone chime on forever. It was a distinctly black and white choice, and one that asked of you just how much you valued a chance to explore free of the leash. To let it ring was to then merge into the crowd and see yourself as just another pedestrian rather than a mere gun-for-hire. To let it ring was to later dance along the railway lines and die from unexpected electrocution.

It’s the unrestrained freedom afforded to the player that has propelled the maturation of the Grand Theft Auto series, even serving as one of the games most outright defining aspects. Grand Theft Auto is the sandbox game, and a canvas for as much chaos and criminality as you’re willing to partake in. Maligned by many and praised by many more, the series has evolved with enough consistency to become the lynchpin of its genre, spawning a host of derivatives and achieving cult status along the way. The only missing piece up until the fourth instalment was an arena in which to fight beyond the realm of the traditional GTA single-player experience.

The multiplayer sidebar of Grand Theft Auto IV offered little in terms of a grand cityscape to mould in the image of you and your cohorts. It was a cooperative sandbox, sure, but one with severely limited tools and a lack of purpose. Red Dead Redemption too suffered with similar problems – it brought players together, but only for the sake of having them tear each other apart. The arrival of Grand Theft Auto Online then, the multiplayer component of Grand Theft Auto V, was Rockstar’s truest attempt yet at capitalising on the collective desire for a dedicated cooperative experience set in the vibrant, violent GTA world. A city run by thieves isn’t too much of a detraction from several of the series’ narratives, anyway. The major difference here is that many of those seeking to murder you are not too far upwards of thirteen years old.

Grand Theft Auto V first released on the Playstation 3 and Xbox 360 on the 17th of September 2013, with the online servers going live on the 1st of October a few weeks later. Initial trailers teased the notion of a rise to prominence from something of a gutter-dwelling thug to an armed and untouchable property magnate. This was the American Dream at the heart of GTA Online, and there was no quaint picket fence or scuffed leather briefcase in sight. Profiteering was done solely by spitting bullets and setting alight whole city blocks. The endgame didn’t exist so as long as there was something out there that you still wanted to purchase. And with an artificially inflated economy lending to the decimation of the dollar, everything you desired brought with it an extensive tax of blood and ammunition.

Come launch, servers creaked and buckled beneath the might of the wave created by thousands upon thousands of simultaneous logins. These were people clamouring to chart their own personal road of ruin. Players tantalised by the prospect of holding their own territory in a city full of likeminded psychopaths. Yet for the first week following the flip of the switch, GTA Online existed only as an apparition. You could see its presence, but to try to interact with it was to be met with a lack of response server-side and a boot back to the menu. Several character corruptions and innumerable disconnections later, and the dust of a tumultuous introductory period was beginning to settle. Grand Theft Auto Online had finally sputtered into life. All that was left now was to chase the dream.

★★★★★

A HUD cluttered with icons and a ceaseless text message feed hardly helped to sway any initial confusion. You began with $5000 in your wallet and the desire to turn that into much more. But the early run-in with that particularly unkind soul already stocked up on explosive bombs meant that your successive hospital bills had bankrupted you before you could even raise your fists in defence. Unable to afford even a single cartridge of bullets in order to retaliate, the missions beyond the free-mode core soon beckoned.

Grand Theft Auto Online was structured as such that your free-mode lobby was an anchor point for every instanced activity that you chose to participate in. Within free-mode, you could pursue bounties, rob convenience stores and pawn stolen vehicles, all the while wondering whether the other players in your vicinity would choose to hamper your progress by rattling you with machine gun fire as you sped across their periphery. Outside of free-mode though existed the bulk of opportunities for which to set you on your way up to the penthouse suite of the Maze Bank Tower, most of which relied on cooperation with other players before it did an avoidance of them. Those chasing fast cash stuck to racing – ‘Down the Drain’ soon became a popular choice for its maximising of money earned over time spent. Similar race tracks set within the boundaries of the Los Santos International Airport and the grounds of the penitentiary also promised GTA dollars in their most easily-cut form. For those seeking far less mundanity and an ease of the grind, story driven co-op missions offered greater payouts but with an equally greater threshold for failure. Racing had procedures in place for allowing those who had dropped to the back of the pack to stay within contention of the race leader. Co-op missions however had nothing of the sort. If your overly aggressive ally decided to spend the entire pool of team lives on being flattened by a tractor and riddled with pistol fire after charging in without assistance, then you were entirely out of luck.

Your drip-feeding of income was largely consigned then to one of two parallels. Some of the more interesting cross-country races available were harder to populate amidst a mass flocking to the aqueducts and prison courtyards. And co-op missions barely offset the quickly grating nature of successive races, particularly due to the inconsistency of the income gained. Progress up the financial ladder was stymied further by the pricing of everything in free-mode. Disregarding luxury purchases, the recall of insured vehicles and your rearmament meant that a few hours lingering in the purgatory of the games lobby system was soon negated by just a few moments of expenditure. If instanced lobbies served as your workplace, then free-mode was the basin in which you flushed your worth away on the necessities required to keep you afloat. And the sooner that you acted on impulse with a purchase of extravagance, the sooner you realised just how little money you had actually earned. Rather aptly, the financial makeup of GTA Online seemed born of the same sense of satire that the series had prided itself on. This time, the joke was on its legion of wannabe crime syndicate kingpins.

Glaringly apparent was the lack of broader source of income that could offset GTA Online’s emphasis on excessive spending. Their implementation aside, the single player narrative of Grand Theft Auto V utilised a series of heists as bookends to the main narrative. You’d spend time deciding upon a way of approach and which staff to assign to different aspects of the job in order to ensure the biggest possible profit. And they’d long since been promised as part of the online environment.

★★★★★

Staggered content updates brought with them further money sinks in the way of new weapons, clothes and vehicles, yet no score existed in order to cover for the absence of Heists up until the time of their eventual release. And by the time that they did, the enthusiasm that Rockstar had expected would accompany them wasn’t echoed by a community long left to toil. Their belated introduction did at least help alleviate much of the dreariness surrounding the games many tired online playlists. And they did so by encouraging cooperation for the benefit of mutual gains, rather than the needless destruction that had become a staple of your average free-mode lobby.

When the Heists update released on March 10th of 2015, Grand Theft Auto V, and thus Grand Theft Auto Online, had been live in its remastered state on PS4 and Xbox One for four months. One month later, PC players would finally get a chance to join in with the games first release on that platform, with the combined editions of Grand Theft Auto V having largely dictated earnings of $2.3 billion dollars in revenue in the period between July 2013 and September 2015. And it was earnings so staggeringly large that made the absence of a noteworthy expansion seem that much more evident. Prior to the addition of Heists, GTA Online had been supplemented with the aforementioned content injections at regular enough intervals with each adding a variety of new customisation options. Missing though was something fundamentally different, something that shook away the cobwebs and breathed new life into the ‘earn, spend and regret’ cycle. And Heists, although different at a glance, only served to echo many of the problems inherent to the game rather than providing a solution to them.

The potential payoff for seeing a Heist to the end was tantalising. The hardest part was simply reaching the finale intact. In order to make it to the money-spinning heights of a Heist culmination, you’d first have to navigate four other missions that weren’t too much of a detraction from the regular co-op missions that you had already run into the ground repeatedly. Ranging from scouting locations to identifying the necessary equipment, setup missions cast a strong light upon two of the poorest aspects of GTA Online that had clung to it even despite its revisions. The first was the artificial inflation of time. Several setup missions asked one or two of the necessary squad of four to break off and sherpa a vehicle or closely tail a target, which was a far cry from the amount of action that the pre-release trailers had emphasised. Many of the setup missions too were weighted in favour of preparation over combat – you’d spend much of your time simply driving between two locations, with the only break in between being a small thirty-second gun battle. The second biggest impediment to your enjoyment was the technical aspect of the Heists. Four players were needed to start any Heist mission, with a fair fraction of GTA Online’s regulars playing in groups smaller than what was required just to try them out. If the player count of your group dropped below four at any point of the Heist then you would be met with an automatic fail and shifted right back to the menu. And you’d meet with the same fate if the pool of team lives ran dry, similar to regular co-op missions. Having to search for a player or two to fill in your Heist group also meant not being able to communicate with half of your team had they lacked a microphone or if you were in party chat. It was a recipe for failure, particularly in the early months when the entire player base was equal in their misunderstanding of each Heist and its objectives.

And greeting every failure was not a chance to reboot the mission again and start over – it was the lingering of the Los Santos clouds, the reappearance of the matchmaking lobby and another search for a hopefully competent teammate. Failing a Heist wasn’t frustrating because of their difficulty. It was frustrating because failure brought with it an arbitrary waiting time. Heists represented a second act for GTA Online, and it was the return to the regular release schedule of the smaller add-ons in the weeks that followed that would finally extinguish any lingering hopes for a single-player expansion. Development of multiplayer content would continue as long as Rockstar had the funds available, and thanks to the success of its own premium currency, GTA Online’s immediate future was on very steady footing.

★★★★★

Funding multiplayer content was a wealth of income via Shark Cards, Rockstar’s own branded micro-transaction payments. As of June 2016 Rockstar had shipped 65 million copies of Grand Theft Auto V making it the most popular game in the series. By the same date, Rockstar had touted a doubling in their sales of Shark Cards which had now earned them little over $500 million in revenue on top of sales of the game. The money poured into the Grand Theft Auto brand had been predictably consistent with every major release, but with Shark Cards came a spike in financial success big enough to clarify what Rockstar had hoped – that people were willing to pay for the immediacy of consumption.

It’d take £65 to net you the biggest Shark Card that Rockstar stock, one that would pad your online wallet with $8 million worth of GTA Online currency. And even with that amount of money, you’d still be priced out of the games two most unapologetic extravagances – the higher end Yachts, and a solid gold Luxor private jet. Shark Cards are a contentious subject because they affected the balance of GTA Online’s financial makeup for everyone, not just the players who elected to purchase them. For those who chose not to exchange their real cash for virtual GTA currency, the importance of maintaining a steady profit over time becomes increasingly evident. In order to purchase a vehicle costing around $750k in-game dollars, then you’ll need to repeat a mission that awards $10,000 once every 10 minutes for the next 12.5 hours. And that’s without expending anything further on ammunition and health replenishing food, or factoring in the many minutes spent searching for that particular mission and others to play it with. The increasing reach of Shark Cards becomes all the more apparent when you also consider how Rockstar have responded to the situation by lessening mission payouts and hiking prices across the board. Certain caricature masks sell for around $30k. Double that, and you’ve got the sum total of a particularly garish dinner jacket and slacks. Too steep to overcome is the market for the player not interested in Shark Cards. Too easy to obtain is everything for the player who is. There’s no middle ground in GTA Online. Either you’re willing to spend the time required, or you’re not. And if you’re not, Shark Cards offer a way out that seems less like an optional extra and more like an eventual necessity.

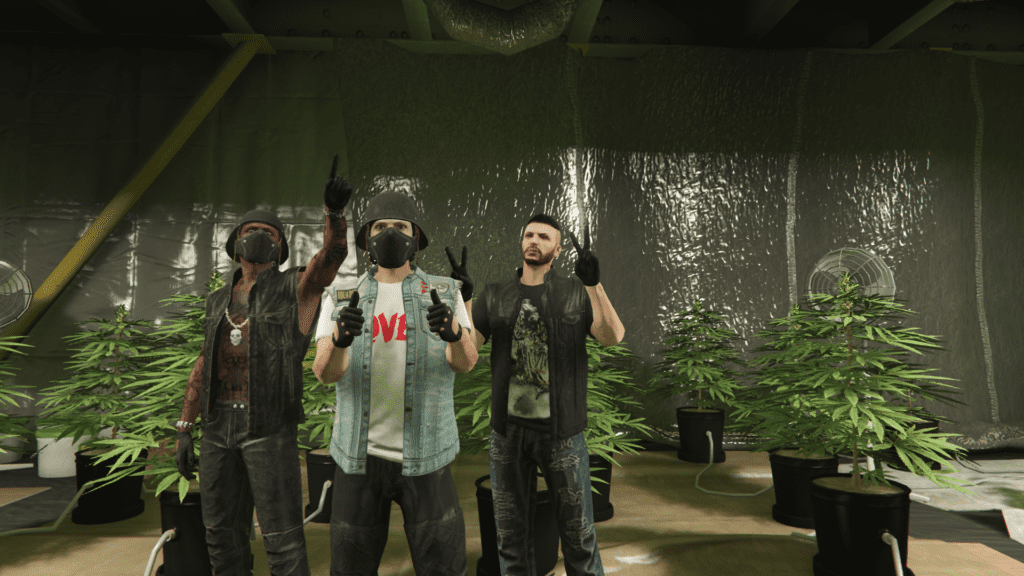

Recent updates to GTA Online have at least improved again on the number of different ways in which you can earn money. In June of this year, the CEO update brought with it the chance to collect and pawn illegal wares all in the company of your fellow upmarket thieves. Then in October came a similarly structured addition in the form of the Biker DLC, which replaced collecting and selling crates of stolen merchandise with generating money through drug manufacture. The aesthetics of each add-on reiterated the best of what GTA Online has managed to accomplish – the element of role-playing by way of character customisation. When working for your CEO, you could deck yourself out in pinstripe suits, spotless loafers and pristine silver jewellery. And in the Biker DLC, you’d trade all of that in for denim cutoffs and a tattered pair of jeans. The tone of each add-on was an enjoyable distraction, but less so was the amount of money you would have to lay on the table in order to be a part of it. As in both DLCs, one person in your group was required to purchase the mandatory CEO office and Biker clubhouse, and in both cases, the most barebones option would set you back a cool $1 million GTA$. And as soon as that amount had been plumped down, the chase began to earn it all back, rather than by increasing your earnings through what the DLC had to offer. Perpetual financial insecurity was just a backbone to what GTA Online had steadily become, with these latest additions echoing the tone of greed that Rockstar’s flagship multiplayer environment had begun to revel in unrepentantly.

★★★★★

Perhaps most damning of all though is the way that GTA Online is set up to allow certain players to always have an advantage over others. And this advantage is usually one that is bought and paid for. Having the temerity to spend time with your crew in a free-mode lobby earning money through ferrying product generated through the Biker DLC is enough to attract the ire of many others with a penchant for ruining fun. The Hydra attack aircraft is the go-to weapon of choice, a piercing bolt of speed and deadliness now comfortably in the locker of many an average player. And should you manage to forcibly pull it from the sky with a hail of thousand-dollar rockets, then its defeated pilot need only wait for a single minute before they’re back in the sky raining fire upon your helpless self once more. And it extends to ground combat, too. Rocket launchers being used as get-out-of-jail-free cards for near enough any situation, Sticky Bombs the perfect choice to pelt someone with as soon as they pull of out the garage in their brand new car. The element of player-on-player grief has existed in GTA Online since its first day of full functionality, the only differing factor being the many ways in which to successfully rid a player from the lobby amidst a needless prejudicing.

And it’s an apt image, that of a Hydra repeatedly bombarding you and your team excessively to evoke the eternal state of Grand Theft Auto Online. On the ground, a team of three or four try to make money by working together and actively avoiding conflict. In the air though, a player with a wallet full of cash earned through either manipulating the newest glitch or purchasing an abundance of Shark Cards needn’t concern himself with anything other than the destruction of that small clutch of blips on the radar. A retaliatory message from the pilot may read something along the lines of “It’s GTA!”, for which he’d be right. This is Grand Theft Auto – the haven of destruction, crime and senseless violence. The difficulty for Rockstar lied in drawing a line between that and the cooperative side of things that attracted people to GTA Online originally. Few aspirations for the mode prior to its release will have pondered the intervention of others over the camaraderie of racing against your friends and robbing banks in tandem. For just as much as Grand Theft Auto was the violent videogame, it was also the game that introduced many to the liberation of the sandbox environment.

Grand Theft Auto Online relishes this freedom. The freedom to go off-book and join your friends in holding back waves of police from the belly of moving train or to try your luck at pedalling all the way down Mount Chiliad without flipping over the handlebars. My best memories of the game will entail these kind of moments, ones free of money hoarding and numbing encounters with other players. GTA Online gave me what I wanted in a Grand Theft Auto environment that I could share with a friend. It was everything else that sought to impede upon that freedom which regretfully succeeded in blighting the experience.