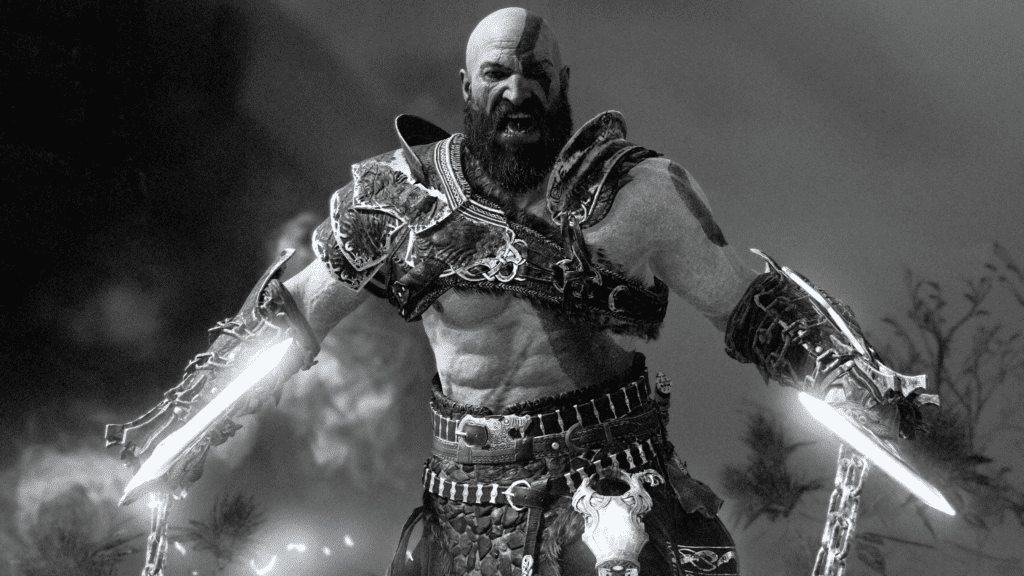

Living in exile and longing for solemnity, the man who walked along the path of retribution struggles to find peace. The Kratos we meet in 2018’s God of War is a soldier after the war, one left embittered and disillusioned by a lifetime of conflict. The bandaged arms where chains used to hang and ash seared across his body are the markings of an instrument of death, baleful remnants plainly unbecoming of a father to a young son. Kratos is a man now free of his bloody desire for vengeance, the cold Norse winds of Midgard dulling the flames of his fury. And though his hatred of anyone who would call themselves a god may still fester, his will for their annihilation survives only in memory.

God of War is the story of a warrior and his child – the journey of Kratos and his son, Atreus, to fulfil the dying wish of his wife by taking her ashes to the highest peak in the realm. Carved across Kratos’ face is the gormless expression of an enduring fighter, every indent and scar a reminder of his suffering at the hands of the divines. Though Kratos has a prior history with the Olympian Gods of the Greek Pantheon, he is not an entirely predefined character. One of God of War’s most impressive traits is in how it embraces its own past, rather than casting it aside. Kratos is still the same man who left Greece on the cusp of a new godless age, is still the same son that killed his father. Though God of War is a story as much about the maturation of Atreus as it is Kratos’ acceptance by him as a living embodiment of destruction.

An age of unrelenting warfare has left Kratos wise to the true nature of godhood, and as his resentment may seem confusing to a son raised on fables of godly heroism and valour, he is unable to deny the past an influence on his decisions. Though God of War is such a stark tonal contrast to the original trilogy, it’s Kratos’ history that gives his character in the present an err of gravity. In his pensiveness and deliberation, there exists weakness. And in weakness of any form does the story of the Ghost of Sparta seem like more of a fleeting legend. But the God of War is still a mortal, and so the series most enduring message feels just as pertinent as it ever was: gods can be killed. And gods are all the same.

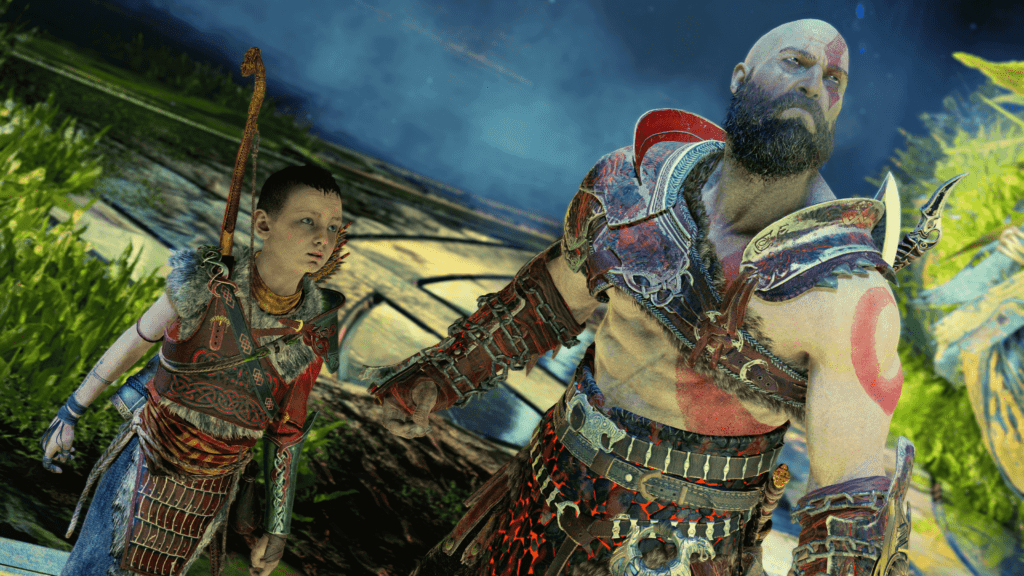

The relationship between Kratos and Atreus is the heartbeat that sustains God of War’s every roaring battle and moment of solace. By the time that the end credits softly fade into view, there’s a sense that both father and son have grown in a way that seems organic and believable. We already know Kratos: he’s a killer, a beast, a harbinger of chaos. But as Kratos can’t even bring himself to place his hand upon his son’s shoulder in order to comfort him, his emotional scarification comes to the fore, and allows for the growth of a new dimension to his character. Kratos fears for Atreus’ safety, not just in the context of a Norse realm brimming with untold terrors, but also from the future that his lineage does promise. So Kratos’ teachings begin in earnest: first in smaller stories that are quickly mocked, then in bellowing bursts of anger as Atreus steps out of line. As Kratos preaches sage advice delivered in a typically coarse and unkempt fashion, the significance of his bloody adolescence becomes a weapon to be wielded for a just cause.

Like every father, Kratos is a teacher. In battle, he will shout down Atreus for a lack of care. And as the two sail to another location, the moral of his story will be punctuated by a bellowing instruction. Every fight successfully fought and Norse rune transcribed feels as though it benefits the strengthening of their bond, their understanding of one another. Though fatherhood initially seems like a foreign concept for the God of War, it’s the contrast between his role as a father and his irreparable relationship with his own that depicts Kratos from such a refreshingly unique perspective.

THE SPARTAN’S FACE TELLS THE STORY OF A LIFE NOT LONG PAST – A BLOODY SAGA, FOREVER INESCAPABLE

As players pore over his tortured visage, a new kind of empathy can be derived for the Spartan. Kratos’ admission of his own faults is met with the resolution to not pass on his anger to another. In seeking to ward Atreus from similar self-destruction, the man worshipped for his mastery in the art of warfare becomes something much more than just a swinging blade.

Distanced from the ruination that he caused his homeland, Kratos’ legacy in the Norse realm of Midgard is nonexistent. Midgard sits separately from the rest of the world. Its politics and its history are its own, with the nine realms that comprise the Norse landscape each offering more personal tales of courage, loyalty, and with a certain inevitability, betrayal. In escaping the freshly-lit fires of Greece, Kratos ventured to a land wrought with its own godly terrors, one that only affirms his preconceived prejudices. The planes of God of War all feel convincingly worn and inhabited, despite corpses seeming more prevalent than the living. In the absence of many notable Norse figures that do not pertain directly to the main narrative, spoken parables and written lore fill in many of the blanks. I found myself cursing the arrogance of unseen gods as their stories were recounted during expeditions, hoping that Kratos would meet them so as to assure their fate became similar to that of the Greek Pantheon. And through these tales grew a greater desire to invoke a lasting impression on this new world, particularly as an outsider ignorant to the conflict that has left the land perpetually smouldering.

God of War is situated during a time for flux for the Norse realm, where the world-ending phenomena of Ragnarok is spoken of in hushed tones and with an underlying fear. In creating a world of dread, where the damnation of the gods has left a permanent blemish on the land, God of War achieves a great permanence in its more darkly tone. As moss and rot clings to the black and gold monuments erected by the gods of old, Kratos and Atreus’ journey feels as though you’re walking through a diorama of Norse mythology, where not even the Spartan with the red streak across his body seems out of place. Wonderfully detailed set design aids in believability beneath the fiction, as everything from the grand expanses of Alfheim’s marble halls to the Norse runes etched into a stonemason’s slabs has been crafted with care. A reserved yet remarkable design ethos remains consistent even as the calm waters of the Lake of the Nine give way to the washed-out pastel skyline of Helheim. And against the immaculate aesthetics of the world that surrounds Kratos and Atreus do the intricacies of the game’s visuals seem all the more impressive.

By the time I was ready to duel with God of War’s antagonist, my once shoddy axe was now decorated with ornate designs and cast in the distinctive mould of a Norse relic. Accentuating a visceral and heavy-set melee combat system are weapon enchantments, pommels and runes that increase stats and alter your offensive abilities.

ATREUS STARES AT THE WORLD EXPECTANTLY. HE IS A CHILD OF FABLES. HE IS HIS MOTHER’S SON.

Rather than just pushing up an arbitrary number, players are encouraged to play around with specific character builds that compliment their chosen play-style. Gems that generate Kratos’ Rage ability are helpful for the berserker, while I opted for a more defensive style that leant on multiplying the damage of thrown axe attacks.

Though certain enemy designs are disappointingly repeated rather than elaborated upon later in the game, the satisfaction that accompanies a successful kill is never in question. Hyper-violent kill animations see Kratos target weakened enemies by pulling them apart at their mandibles and crushing their skulls beneath the sole of his boot. And as you progressively improve the Spartan’s weapons and armour, those gory finishing blows begin to seem more commonplace in combat. Part of improving Kratos’ gear is in shedding the rust from the God of War and helping him recapture the strength of his youth. As enemies begin to fall a little easier and with a more cultured style of attack – both to Kratos’ axe and Atreus’ bow – the growing bond between the two continues to blossom even outside the narrative.

In God of War’s impressive menagerie of interconnected mythology exists a very personal story of a father and his son. Though the Norse lore may seem daunting with its confusing lineages and many realms, it never swallows you whole, the narrative instead focusing on a personal relationship that is in parallel with its rotten fantasy, rather than at the exception of it. Through the intimacy of the story, we become truly concerned for the fate of our protagonists. As tales of gods slaughtering their own permeate adventures through the Norse worlds, the mournful god-killer is, for the first time, truly vulnerable. Deep in the quiet lurk the horrors of this new land, and though that’s where many of them remain, the stories that outline their barbarism are a testament to the consistently wonderful writing that carries both the plot and lore.

God of War makes terrific use of its action set-pieces, but it’s telling that the game ends upon a quiet conversation rather than a hectic battle. This was not a pursuit of vengeance or a quest for destruction. In fact, any antagonists were merely roadblocks impeding the father and his child from spreading the ashes of their beloved. Kratos’ bellowing of “Boy!” in the direction of Atreus was a note that the game reiterated, justifying the Spartan as a man of few words and little time for compliments. Kratos was born for war, moulded in bloodlust and defined by a penchant for murder. As he unfurls the bandages upon his wrists exposing the scars of his past, he finds an acceptance in himself that he has never held before, an acceptance held in earnest by his son. So the God of War puts an arm around his shoulder, and the two of them begin the journey home; a remarkable, fascinating story that ends as it means to go on.