America’s destiny had been made manifest and the West was wild no more. As the frontier expanded with the growth of industry, the gangs and gunslingers in opposition to progress were hunted as outlaws. And when the hunted fled, the law did follow. The story of Red Dead Redemption 2 is told during a time of change, where the cannons of the Civil War stood silent and the reformation of society began. Expansionism reigned, and it did so without relent. Occupying the perspective of bandits and murderers maligned by an inevitable fate, the tales told across Rockstar’s Red Dead Redemption series read like two distinct commemorations of the same era. In the original, John Marston’s past transgressions were exploited so that the remnants of his former brotherhood could be eradicated. In Red Dead Redemption 2, a sequel that takes place prior to the events of the first game, the last few warriors of the West count the days that they will remain together as they traverse the land driven by the fear of persecution. Before Mexico and New Austin, there was Lemoyne & Scarlett. Before John Marston journeyed across borders on behalf of the Bureau, he fled together with his wife Abigail, their young son Jack, with Dutch van Der Linde and with Arthur Morgan.

A long time removed from Rockstar’s last title, Grand Theft Auto V, Red Dead Redemption 2 arrives boasting an inexorable sense of self-assurance that’s typified by how earnestly it holds itself. Even as a reimagined Los Santos glowed with authenticity and teemed with life, it was never free of its roots in parody. The game’s attention to detail was absolute, but the colourful hyperbole with which the world operated was inescapable, even during times of apparent levity. Grand Theft Auto V was a heavy handed criticism of modern culture, and it would remain committed to this idea even to its own detriment. In the modern San Andreas, cynicism prevailed above all else. In Red Dead Redemption 2, the cynical are not just the disillusioned, but the fearful, the regretful and the downtrodden. Prosperity has passed by the land’s wayfarers, and be it by the brunt of the law or a refusal to adapt, their’s are the lives that will suffer. As the game commences, things are already at their worst; a botched heist has led to a handful of casualties, and morale has taken a hit. But the steadfast head of your outfit tells you that everything is going to be okay and that paradise is still within reach. Beaten back by the storm, the curtains raise with the gang mulling the repercussions of their leader’s misjudgement.

A career criminal raised at the side of elders Dutch van der Linde and Hosea Matthews, protagonist Arthur Morgan is introduced as a raw and uncomplicated picture of Western grit, one who walks with a gait that betrays his years and who delineates conversation with all the grace of an agitated Bison. Old enough to understand the implications of change but young enough to yet resist them, Arthur’s story is evocative of its time, and of the collective he belongs to. But he is still a killer, still an ever-defiant opposition of the law, and so he encapsulates a familiar blend of anti-hero even in spite of the game’s renewed perspective. There’s no shedding the rigid archetype of the Rockstar protagonist, with Arthur’s grey morality and flourishes of fury traits that are shared by many of his contemporaries. In order to justify his actions, such a penchant for murder is pinned on an apathetic approach to living, elaborated on no further than with a few sloppy snippets of dialogue and a reiteration of the game’s ‘us versus them’ mantra. Prised apart from such contradictions that scarcely seem to exist outside of cut-scenes, Arthur’s characterisation is typically outlined by the gang’s escalating grasps at freedom, and the sobering strikes of resignation that follow. After the shedding of its prolonged introductory sequences, Red Dead 2 settles into a comfortable rhythm of chaos and its consequences, Arthur’s grumbling indifference gradually giving way to passionate indignation. Torn between an acceptance of reality and a reliance upon blind deliverance, the burgeoning conflict of Arthur Morgan is told with a compelling sense of style and wonderful confidence, even as the character struggles to secure a more striking sense of individuality during moments parted from the company of his cohorts.

THE WILDERNESS PROVIDES – HERBS CAN BE MADE INTO POTENT TONICS, OR USED TO SEASON FOOD

As you wander out into the staggeringly beautiful wilderness, stopping to take in the sights at industrialised trading posts and quaint mountain towns, the only welcome that’s assured is the one waiting for you at camp. Bedded down away from prying eyes, the group’s encampments are hallowed ground, places to revel in each other’s company and forget for a time the blood spilled in order to get this far. It’s here where you’ll take stock of your adventure, the moments of pause offered by the holstering of guns and boiling of the stew pot a calming detraction from the war outside its borders. As one member patrols the perimeter on guard duty, for the rest, it’s time to gather around the hearth and lose themselves in mutual harmony. A linchpin between the mesh of personalities, your Arthur Morgan can choose to be kind or spiteful in conversation, embracing or scorning your camp-mates with a devilish irregularity. Yet it’s with great ease that the characters at camp will endear themselves to you, every heartfelt greeting and playful chide helping to humanise your band of marauders and lift their veil of villainy. Meted over in casual dialogue, their unique histories and future aspirations bring to life the entire ensemble, with a deceptively substantial amount of characterisation colouring to life each member’s prevailing disposition. Depositing an amount of cash at the tithing box was probably what brought you back to camp, but it’s the individuals of the Van der Linde gang that will keep you tethered to the campfire for a long while.

Among the miscreants with whom you share your fate are remorseless killers and stubborn drunks, loveable scoundrels and harmless con artists. In camp, ignorance is most certainly bliss, with the collective sense of contentment and relative normality an insistence reiterated by the gang’s leader-in-chief. And at the heart of the grounds is where he stands, the charismatic master of your destiny, one Dutch Van der Linde. We know how it’ll end for him, of course. The success of this sequel’s story is in how captivating his fall remains despite a pre-written fate, and of the retrospective comprehension we’re given to the antagonist we first met as John Marston.

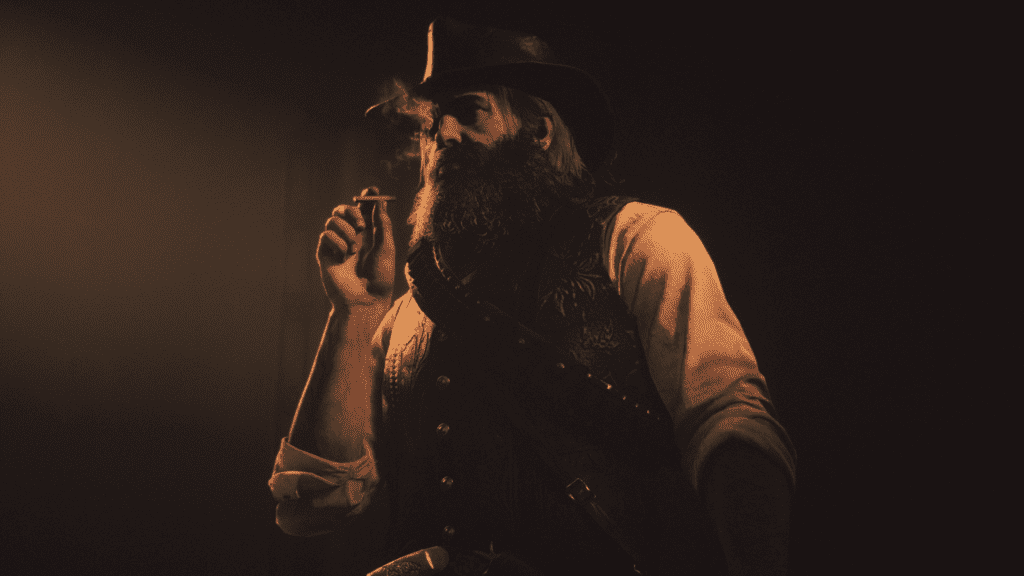

In Red Dead Redemption, a defeated Dutch, his psyche completely uncoiled, waxes lyrical about his own inconsequential place within the world before willingly succumbing. Here, the man still in control of his future dresses in ornate finery and smokes expensive cigars. He reads philosophy and speaks with unfettered desire. And with a sorrowful tone expertly delivered by actor Benjamin Byron Davis, he beckons his followers to his call, lamenting their luck and imploring them to continue on. Charming to a fault and imbued with a dauntless sense of self-confidence, Dutch doesn’t hide his intentions and acts as though he is impervious to the ramifications of failure. The point where determination meets desperation is where Dutch carves his mark on proceedings. Slowly having his layers of surety worn away, Dutch becomes the antithesis of Arthur Morgan, trading realism for faith at a deathly cost. Dutch’s story, like that of Arthur, is one of fear, but of a different way in which to confront it. And an intoxication at the hands of fear is thus where the end begins for Dutch Van der Linde, where the enthralling devolution of his character commences, and where a tremendous respect for his history in the series is paid.

The resources required to support a group of twenty people aren’t so easily gathered, with Dutch demanding that the individuals of the camp all earn their keep by contributing to the tithe box. Thankfully, there are a multitude of different ways to earn a bit of cash in Red Dead 2, and plenty more ways in which to spend it. With hunting and fishing allowing you to feed the camp directly, the spoils of every hunt can be sold for a profit to any butcher or utilised in the crafting of bespoke clothing. And if you’re inclined to assist the law under the guise of a concerned citizen, then partaking in bounty hunts can also help line your wallet with a healthy tinge of green and silver. Next to some of the more structured activities available, there is perhaps no greater way to increase your income than by freely exploring the world. Hidden in cupboards and outhouses, chimneys and lock-boxes are all manner of valuables waiting to be pawned, with every structure marked on your map hiding something of worth. Though the questionable methods used to increase your wealth are all for naught unless you’re willing to spend it with liberty.

FROM VALENTINE TO RHODES, EACH TOWN DEPICTS A DIFFERENT PEOPLE, A DIFFERENT WAY OF LIFE

Starting at camp, you can upgrade the quality of furnishings and stock the shelves with all manner of useful provisions. While in every major town, tailors are available to assist in the refining of your look, with blacksmiths on hand to maintain and improve your ever-growing collection of weapons. Amassing a sizeable fortune isn’t particularly difficult, with a lot of cash naturally finding its way into your lap one way or another. Impressively, your bank balance holds little sway over how much of the game that you get to experience. Rather than a need for money fuelling my adventures, it was instead the array of hunting pursuits and survivalist challenges that kept me involved in the world outside of the story. Taking in a performance at the Saint Denis theatre or bedding down for an extended session of riverside fishing became forces of habit, my revolvers scarcely seeing the light as the game’s possibilities continued to unfurl before me.

Reaching out towards every corner of the horizon, the sprawl of Red Dead Redemption 2 is richly detailed and abundantly sincere. Breathtaking to behold across its dense wooden thickets, snow-capped peaks and verdant farmland, the game’s world is a versatile clash between untouched pockets of nature and the encroaching monopoly of industry, met in the middle by a distinct post-war scarification. Stitched into the fabric of this final glance at America’s 19th century is a thoughtful consideration of the land from every angle, one that’s delivered with such an imperceptible sense of conviction that it borders on the obsessive. And the scope of its detail isn’t limited to just set-dressing or environmental design, to weather effects or projectile gore.

Down to its smallest minutiae, Rockstar’s aesthetic direction lauds the extravagant without sacrificing the authentic. Weapons, carved deep with baroque designs and gilded metallic finishes, cloud with the muck and grime of persistent use. Florid lettering adorns the labels of provisions that line store shelves and imperfections are checkered along the rim of Arthur’s signature leather hat. As the bark on the trees shears when struck with weapon fire and scurrying wildlife weigh down the bulrushes, the technical achievement of the game is undeniable, with the breadth of its faultless detailing ensuring that the world you inhabit never compromises its integrity.

Most impressively, its open-world is one removed from the genre’s typical sensibilities, a freeing exploration of escapism that isn’t suffocated by a mass of restrictive tethers. In Red Dead Redemption 2, content isn’t fastened exclusively to map-markers and excessive directional pathing doesn’t dictate a preferred route of travel. Instead, it’s the lack of information that makes certain elements of the game’s structure feel like such a stark detraction. Other than the occasional tutorial pop-up that hangs in the upper-left corner, information is relaid to you organically and irregularly. And as your understanding of the world grows, it becomes reflected in the pencil scratches that gradually populate your personal map, denoting everything from animal grazing areas to the location of observable rock carvings. With so little emphasis on signposting, interactions with the world are made all the more enjoyable for their unexpectedness. On one occasion, a chance encounter with a stranger lamenting an indecipherable treasure map led me to pick it from his pocket, the map sending me in the direction of four successive clues that concluded with the unearthing of a cache of valuables. That distraction lasted two hours, taking me across a large swathe of the land and past several points of interest that I never knew existed. And it all stemmed from the blooming of a small grey dot on my compass that only appeared contextually. In placing so much emphasis upon the freedom of discovery, the game-world forgoes the need to condense its every facet into a series of interactive checklists and levelling gauges. Instead, the player is at its mercy, lumbering through its lands at a gradual pace and with little control over its unerring wilds. In that, the dangers of the world seem substantial, and Arthur Morgan’s susceptibility to it all is thoroughly invigorating.

REMOVED FROM FREQUENT SHOOTOUTS, ACTIVITIES LIKE FISHING & POKER ARE A WELCOME CATHARSIS

However confident that Arthur may be at dispatching foes, his brutalism is plainly devoid of any finesse, the controls of Red Dead 2 severely lacking in subtlety. Moving your character is inherently unreceptive, with a laboured motion dictating that even the most simplistic of interactions becomes an exercise in patience. Rifling through the pockets of the recently deceased, Arthur lifts the body with one arm and inspects every pouch with the other, before loosing his grip and dropping its mass to the floor with an audible thud. After surviving a shootout, the first question posed is not whether you should to plug up your own leaking wounds, but rather if you’re willing to spend the amount time required to ransack the mound of tattered dusters left in your wake. Exhaustive and elaborate, the motions that comprise Arthur’s interactivity are designed with a familiar attention to compulsive detail, yet are undermined somewhat by their uncompromising implementation. Though Arthur’s deliberation is enjoyably realised when stared at from afar, it can quickly become irksome as you’re regularly subjected to the same recurring movements. And as remarkably detailed as his every motion may be, there remains a distinct roughness to his manipulation that hinders an otherwise streamlined approach to accessibility.

Rockstar’s Red Dead Redemption 2 is built to embrace the wanderer. Its world, free of the obligatory and the insistent, doesn’t ask to be plundered or charted to a fault. Instead, your experience as part of the lifestyle it conveys is unhindered, and your passive involvement in its world enough to engage in the themes it presents. Forcefully prying itself apart from the reiterative aspects of the quintessential open-world, Red Dead 2 achieves an impressive sense of originality that can be attributed to the way that it approaches many of the genres tropes. And in doing so, the game also succeeds as a departure from even Rockstar’s existing template for the modern free-roam RPG. In many ways, the game is a stubborn stalwart for prevailing design sensibilities – the aforementioned clunkiness of the controls that pay little consideration to more refined movements, the typically uninventive structure of mission that culminates with a shootout and a chase. But with so much more conviction does the game change itself in order to impart something new, something that we haven’t quite experienced the likes of before.

With a plethora of different ways to help the gang members that I’d become so easily beholden to, I willingly strived to do everything in my power in order to keep them ready for the battles yet to come. On route to the location of my next chosen mission, I would adorn my horse with pelts and fill my satchel with meat. I would take a detour to the nearest lake in the hope that I could hook something colossal. And then I would fence my sackful of stolen goods, bringing with me back to camp a stack of bills and enough food to sustain an entire Union regiment. This is where Red Dead 2 flourishes, where its intentional diversions and glacial pacing effortlessly ground you in the surrounding world. And its immersion is organic, settling you into a lifestyle of placid verisimilitude that’s only ever upended by its layers of meaningful tragedy.

There are certain issues that life the veil entirely, though. A lofty bounty on your head will generate lawmen that search for you, but such a meagre inconvenience is made all the more trivial by being easily scrubbed at any post office. Meanwhile, the game’s Honour system is notoriously blind to the notion of self-defence, much to the detriment of the entire village that considers a simple misfire an act of war. The fraying present at its edges is where Rockstar struggles to meld together past perceptions and renewed ideas, where a collision occurs rather than a seamless integration. Its ambitiousness is imperfect, but also what most aptly characterises it. And amidst that ambition lives the intangible sense of belonging that Red Dead Redemption 2 best personifies. As one era reluctantly gives way to the next, it’s the marriage between the narrative and environment that forms the basis for such a wonderfully realised portrayal of existence.