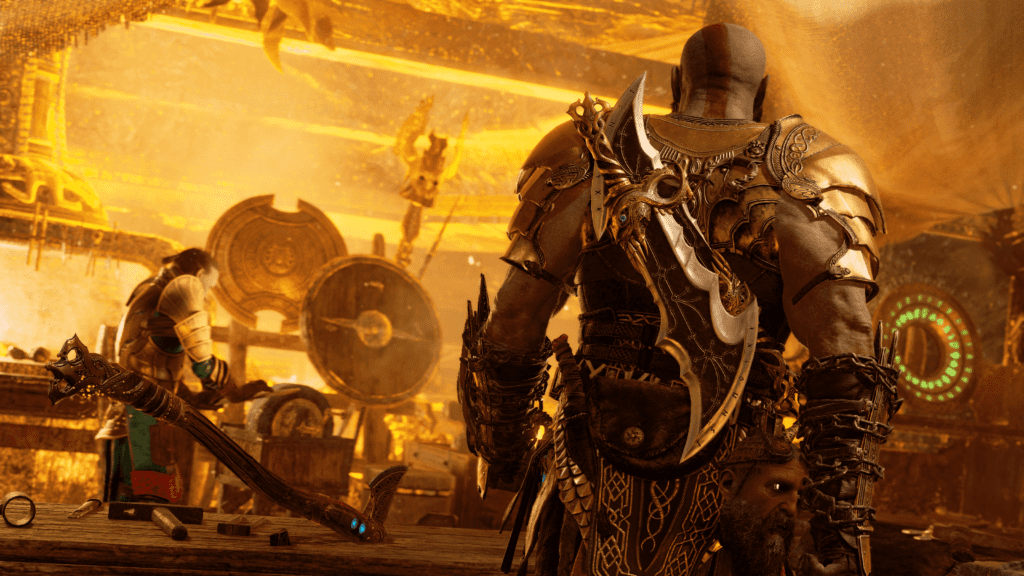

Golden halls slathered in a fresh coat of crimson, the Spartan’s vengeful fury is held in time. In God of War, as in a rising number of titles before it, every battlefield is a different stage in the search for the ideal frame. Separating the in-game camera from the shoulders of our protagonist lends much to the size of the surrounding world – Kratos and Atreus journey to the mountaintop via dimensional pathways and Norse monuments, traversing land and sea as they ascend the branches of Yggdrasil. The beauty of God of War is irrefutable, but immortalising it within the bounds of a passing moment makes for a challenge as perilous as any Valkyrie. The ensuing struggle for perfection is just part of the appeal.

Collecting pictures snapped through a virtual lens is but another way in which we’re able to take ownership of our experiences. Badges such as PlayStation trophies sit pretty on our digital mantles, accomplishments in completion that boast a dedication to the absolute. Meanwhile, the much maligned video-game backlog serves as its own conquest – a challenge steeped in a similar sense of personal pride. Virtual photography, like those aforementioned examples, and even as in writing, offers its own distinct catharsis when it comes to recollection. At a time when visual fidelity is at its most immaculate and the artistry of game design is flourishing, video-game capture serves as a stylistically assured extension of the medium. In the prevailing beauty of the modern game, it’s photo-mode that provides the tools required to admire the digital world from every angle.

Putting the camera directly in the hands of the players is where the self-expression behind virtual photography thrives. Using depth of field modifiers, lighting gauges and post-processing filters, a solitary moment captured in frame can be portrayed from a number of different viewpoints. With the construction of an image being left entirely to the whims of the photographer, landscape photography, character portraits and action shots can all be meaningfully achieved from both a traditional approach, or even a more esoteric one. The freedom to take photos in your own desired style is perhaps the most integral aspect behind the player agency that defines virtual photography. And though the subject matter of a particular game may be the same for everyone peering through the digital aperture, the variety of perspectives captured are never without their own pervading stamp of individuality.

It was in 2005’s Gran Turismo 4 that the virtual photographer’s toolkit was first included as a native accompaniment. A few years later, Bungie’s Halo 3 allowed for image capture through its popular Theatre Mode, with the game’s official website also doubling as a community gallery and hosting platform. Since the passing of console generations, the steady stream of video-game photo-modes on offer has become something of an irrepressible torrent, with 2018 alone seeing virtual photography represented in games such as Insomiac’s Spider-Man, Codemasters’ ONRUSH and Rockstar’s Red Dead Redemption 2. Though there was perhaps no game that I enjoyed photographing more than Sony Santa Monica’s God of War – the story of Kratos and Atreus one that was greatly emboldened by its enchanting mythological setting, and defined by the dedication with which it portrayed Norse legend.

* * *

Having left the Greek pantheon in his wake, Kratos’ story recommences between the walls of a humble hearth nestled deep within a whispering woodland. Besides the delicate cowl of snow that clings to the forest’s canopy and the small runic symbols etched into the tree bark, the Spartan, in his isolation, lives far removed from the smouldering relics of Norse history. God of War unveils its landscape with a steady hand, gradually retelling the legends that have left the nine realms in a state of flux. We’re told of Odin and his son Thor, two familiar names that hold dominion over every winding river and jagged mountaintop within reach of Yggdrasil’s roots. And piece by piece, we’re led to damn the arrogance of their deceits as the truth behind their godhood is revealed. It’s with great apprehension that Kratos, flanked by his son Atreus, ends his self-imposed exile and begins venture forward. One father and son follow the path of destruction left by another as the world’s fate becomes separated from its fiction. Through the eyes of Kratos, the lies behind the fables are unravelled, and the lands ahead are imparted in all their ruinous splendour.

Where once stood opulent masterpieces built in reverence to the gods, now stand crumbling obelisks of stone. The world ahead of Kratos and Atreus is unknown to the both of them, but not to its herald, Mimir. It’s with a disconsolate tone that Mimir, once an advisor to Odin, regales Kratos and Atreus with an unabridged history of the realms. Recounting every death and deceit orchestrated at the hands of the gods, the destruction of the worlds ahead is one all too familiar to the God of War. Here, in the Norse realm, Kratos is but a witness to the raw chaos that divine might encourages, the past at his back as much a lesson in the misuse of power as the desolation to his fore. So wonderful is the game’s mythological depiction when paralleled against its own reluctant decay, that the discovery of every hidden secret felt as though I was salvaging a part of its history.

Buried beneath snowy verges and locked behind ancient, creaking mechanisms are the languages of the Norse forebears, their tools, and their stories. And across every realm exist the scars of godly wrath enacted by the Allfather and his kin. In Alfheim, home of the elven race, crystalline skies and luminous chapels are juxtaposed against bloodied marble halls and droves of corpses, the war for the light eternal as their plight remains unheard. In Helheim, land of the dead, the deceased pack the roads that lead to the City of Hel, wandering aimlessly in the jade murk as the doors to Valhalla remain closed. And in Midgard, home of the human race, golden monuments rot and terrors roam across the horizon, the remains of the living exhibited only by mounds of bone and hoards of untouched treasure.

The lands of God of War are raw and untamed, visions of a mythology where gods walked among the living and monsters cohabited with mortals. Though the game is tremendously faithful to its mythological source material, the Spartan’s place within its growing lore is not without purpose. On the cusp of a great schism, where Ragnarok is set to bring about an end to what remains, Kratos’ influence upon the world’s history is unmistakable, the stranger in the strange land seeking only to fulfil the last wish of his beloved. Of the beautiful demise that it depicts and of the one yet to come, God of War’s worlds were a perfect fit for the virtual aperture, moments in time that were made to endure.