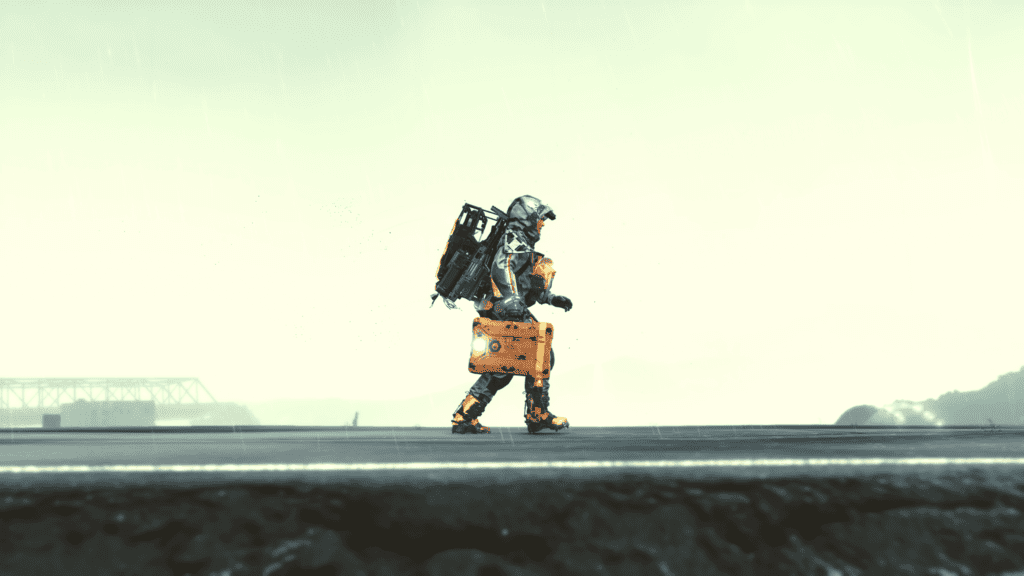

Step by measured step, you begin to weave something from nothing. With every rainstorm navigated and stream surmounted, the prospect of reconnecting a divided America becomes a little less daunting. A lone courier in a world torn apart by a supernatural phenomenon, you and you alone are left to rethread the remnants of a fractured country, unifying all that has been divided. What starts with the placing of a simple ladder evolves into the construction of snaking highways—obstacles along the route to progress overcome through your own endeavour. As you venture through sodden valleys and across glacial peaks, Death Stranding asks you to find meaning in the moments of reconnection that define your journey across the continent. And more than the star-studded billing that adorns the game’s central characters, the depth of its message is best evidenced by how the surrounding world changes in the face of a collective ideal. Previously untouched grasslands now bear the imprints of footsteps and the markings of modern technology, each implement having been laid down by another player that you will never otherwise meet. A bridge over a rocky crag, a climbing anchor down a sheer slope, a generator to charge a sputtering battery—though you may be alone on your travels, it’s the prevalent echoes of other porters like you that encourage you to keep forging forward.

Occupying roles both major and minor, the world of Death Stranding is full of easily recognisable faces. You’ll get used to two of those especially, with Lea Seydoux starring as fellow courier Fragile, and Norman Reedus taking the helm as protagonist Sam Bridges. Along with a supporting cast that features the likes of Mads Mikkelsen, Margaret Qualley and Tommie Earl-Jenkins, the Death Stranding playbill is impressively stacked, its roots in film exemplified by both an investment in acting talent and the heavy directorial presence that permeates every scene. On a shot-by-shot basis, a measured approach to composition along with a host of technical subtleties elevates the quality of such moments significantly, the game’s visual direction remaining unmistakably assured. Such care and consideration given to the design and execution of each sequence is indicative of game director Hideo Kojima’s commitment to style, but it largely comes at the cost of narrative weight. Often, the collection of characters that you’re introduced to feel too far removed from the subtler, softer emotional resonance that accompanies you as you travel across the land. And there’s little merit to be found in characters named for their own dispositions being made to fawn over glaringly vacuous dialogue. For all of the attention to detail that characterises the game’s visual design, its story is imparted with all the grace of a plummeting anvil. As a purely narrative-driven experience, Death Stranding poses more than it promises, raising and deflating your aspirations for substance with a disappointing regularity. Only when you’re free of its flailing theatrics does the game strive to convey the best of itself, and when it does, the basis for its socially-charged storytelling begins to take on a greater importance.

There is little glamour to be found in your role as a courier. In Death Stranding, a remarkably simple gameplay loop typically poses only a single objective: take packages from one location, and deliver them to another. What makes such a basic premise so interesting, and what represents the crowning achievement of a game that seems comprised of two wildly different halves, is the way in which the world evolves to cater to your task. And it all begins with little other than a pair of boots and a packaging harness. Ahead of you, an untamed land beckons, one in which entire mountain ranges have risen from almighty tectonic collisions and jagged fault lines scar the earth. Built directly into cliff faces and nestled away on secluded prairies, survivor enclaves populated by the wounded and weary inheritors of the post-apocalypse await your arrival at their door. Navigating the dangers of the world in order to reach a destination unscathed represents just part of the challenge. In order to ensure that their packages remain intact, you first need to understand the limitations of the lone porter, and the become familiar with the delicate balancing act that dictates the transporting of cargo en masse. Should a slope be too steep or the tower of parcels clinging to your back too tall, then you’re liable to fall to the ground, damaging your load in the process. Death Stranding puts a lot of emphasis on not just reaching your destination, but doing so in a way that minimises damage to your products. A straightforward two-button system helps you realign your centre of gravity on the fly, while your personal scanner, the Odradek, can be used to reveal whether or not a surface will be easy to cross.

IT’S GOOD TO GIVE BACK. JUST AS THEIR GENERATOR AIDED YOU IN YOUR MOMENT OF NEED, SO WILL YOUR BRIDGE HELP THEM IN KIND

What initially seems like a frivolous distraction is actually better understood as an extension of the inventory management system. Everything you choose to take with you, from delivery items to personal defence armaments, need to be attached to your person, meaning that there’s little room for excess if you’re planning on making the most of a single trip. The better you align your cargo, the easier it will be to traverse certain paths, and if that means heading out unarmed in order to shed a little bit of weight or improve your balance, then you may find that it was worth taking the risk. It’s an admittedly odd thrill to decide upon a route across foreign territory and then arrive at your destination unscathed. Settling on a specific pathway makes every subsequent trip that little bit easier, and after a time spent retreading your own footsteps, the grass beneath your feet begins to give way to muddy tracks. Your progress here isn’t just being measured in your dependability as a courier. As your mastery over the land gradually improves, so does the way in which you approach it become more direct, with Death Stranding celebrating your ingenuity in such a way that progression becomes inextricable from your own pursuit of efficiency. The greater the reverence that you begin to command, the more that you are encouraged to push yourself to that carry that little extra, or subject yourself to a little more danger, all for the sake of a glowing review. Your latest delivery may have been the most treacherous yet, but it will have ultimately been worth it if only to plug up that rocky boneyard with a web of ladders and rope hooks to aid you on future missions.

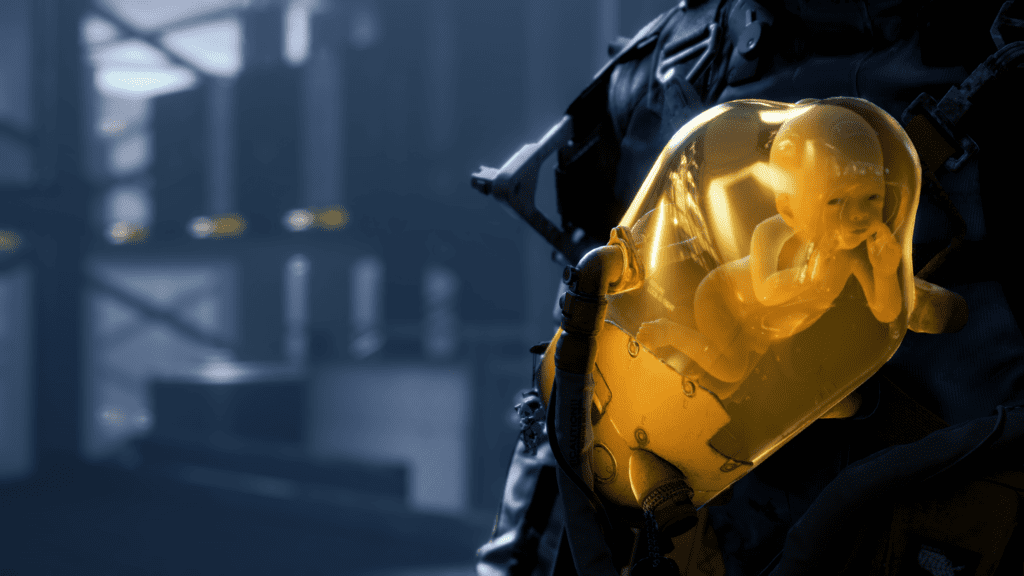

Your primary goal then is to deliver packages to distant locations, and in doing so, connect survivor bunkers and distribution centres to a wireless nexus called the chiral network. The moment that a location becomes connected to the network, you then gain the ability to construct emplacements on the nearby land. And as soon as a site goes live, your world becomes instantaneously populated with a smattering of structures created by other players, the asynchronous multiplayer features of Death Stranding broadening with every successful voyage to newer pastures. In order to successfully bring a location online via the network, you must first make the trip free of any aid offered up by your fellow porters. That means traversing without any signage warning you of phantoms lurking in the nearby thicket, and crossing rivers by your own means rather than waltzing over them atop player-made bridges. Other than the rugged unpredictability of the environment, the two things most likely to turn a simple delivery run into a frantic fight for survival are Mules and BTs. The former are human couriers driven to a state of madness by their fixation with hoarding packages—something not at all difficult to empathise with given the ease with which delivery quests are undertaken. And while their aggressively territorial nature means that you will regularly find yourself on the wrong end of their electrified pikes, their threat isn’t comparable to that of the spectral apparitions that inhabit every downpour.

BTs, or Beached Things, are the ghostlike beings responsible for the heightened consequences of death that affect the world, their presence turning potential cadavers into the explosive time-bombs that seemingly devastated the entire continent overnight. Some of the most fascinating aspects of world-building within Death Stranding revolve around the implications of BTs, with many notions as to their origin and purpose still subject to much conjecture. Not just due to the lack of understanding that surrounds them, BTs evoke a potent sense of horror that feels perfectly paired with the game’s natural melancholy. When alone, it’s often the burgeoning soundtrack that wills you forward, with its soft, reflective tones enveloping you in a contemplative sorrow. Conversely, as soon as the rain begins to fall, the sharper, more outwardly vivid pangs of horror take over, your scanner reaching for an invisible presence as you instinctively freeze in place. BTs take humanoid forms and look as though they’ve been pieced together from thousands of obsidian fragments. They hiss and growl in your general direction, and they wail in an untold agony. BTs look like conventional spectres, but move with desperate lunges and behave with the disconnected mannerisms of other-worldly beings. The most important aspect of their design is that you don’t need to understand them in order to fear them—but that won’t stop you from trying as you progress deeper into the story. BTs are a thematic extension of the unknowing ahead of you, and the terror they evoke is palpable from the moment that a single droplet of rain rolls off your shoulder. They’re a necessary evil, and one that helps to balance the delineation of hope with regular servings of darkly dread.

A large part of the Death Stranding gameplay loop revolves around overcoming the challenges of a treacherous environment, but the tools at your disposal offer much more than just a helping hand with steady footing. Alongside popular implements such as ladders and bridges, you will gradually gain access to a surplus of equipment that aid in all aspects of delivery, from the speed at which you’re able to travel, to your effectiveness in combat when tasked with defending your load. Using the multifaceted PCC kit, you can create things like watchtowers, which allow you to survey the horizon for points of interest, postboxes, which you can use to entrust cargo to other porters, and even personal rest-stops, pop-up safe-houses that can offer you some welcome respite when caught out in the wild. Vehicles like the Trike drastically alter the speed at which you can cover ground, while the Bridges truck brings with it the single largest cargo carrying capacity in the game. The diversity of equipment and the beneficial application of it can make for some truly endearing moments of triumph, especially as you realise that the tools you settled on were the exact things needed to execute a delivery without a hitch. Preparation and preparedness hold significant sway over a porter, but rarely do you feel cheated when things don’t go your way. You may find that your cargo has succumbed to a debilitating level of damage from an onslaught of acid rain, but with no shelter in site, the difference between success and failure may only be a few extra containers of repair spray. Similarly, as you and your packages tumble across the snowy tundra, hooking a levitating cargo trolly to your hip may be a preferable compromise that at least allows you to get where you’re going free of any further harm. It’s with little warning that the once uncomplicated task of delivering a package can evolve into a fantastical multi-stage excursion, one that relies upon the use of everything from smoke-emitting decoy cargo to grenades synthesised with your own blood. Alongside the breadth of options that it offers the budding deliveryman, the game’s understanding of its own systems is espoused by the confidence that it places in the player’s ability to grow with them. Free of any unnecessary impediments, the core of Death Stranding is imparted in its whole, a veritable toy-box propped at your feet with few restrictions and even fewer flaws in implementation.

YOUR WORLD EXISTS THROUGH A COMBINED EFFORT, AND IS WOVEN TOGETHER FROM HUNDREDS OF SHARED EXPERIENCES

The relationship between player and environment is catalysed by the game’s social elements, with the interconnectivity of Death Stranding serving as a fundamental part of the experience. Not only is it rewarding to make your own mark on the land, but it’s also gratifying to make use of the structures put in place by someone else, the small part that they played in your story something that fosters a great kinship with a community of likeminded porters. Often, an otherwise inconsequential generator can make or break a delivery, particularly when there’s still plenty of distance between you and your destination. For the player that originally placed it, maybe they did so only to shed the weight of a PCC kit from their load. But for you, that generator can be the saving grace of a multi-hour trek, powering a vehicle at the very last as its battery finally fizzles out. Even structures that you would otherwise never intend to use can make for welcome additions to your world. My primary route through the heart of the reach had me recognising bridges and postboxes by the name of their authors, names that quickly became as important to me as those of my litany of clients. Like mile markers and roadside signage that kept me heading in the right direction, their involvement in my mission was minute, but significant enough that I had passively committed those dozen or so names to memory. And the prospect of having a similar impact on someone else’s world was what inspired me to do more. Death Stranding evidently places a lot of stock in these connections, with the way in which it encourages such selfless behaviour a testament to just how much of your journey is reflected in the shared experiences of others. Previously contented to commit very little, I found myself taking an extended break from the narrative in order to pave roads through dangerous territory, my reward being that of over a hundred different players utilising my creation to fulfil their own objectives. Being showered in likes and having my social grade improve was a fair reward for my efforts, but it was no more fulfilling than being reminded that there were other players out there walking parallel to me, hiding from the very same rainstorms and treading the very same tundra.

What Death Stranding achieves in social cooperation is remarkable, especially given its asynchronous approach to player interaction. No less than fifty hours into the game, my experience was outlined by those smaller moments of connection, stories of successful deliveries brought back from the brink of failure by the endeavour of others. This made all the more impressive by how effortlessly approachable that the game remains throughout, its learning curve an education in reciprocity above all else. What Hideo Kojima has accomplished isn’t a structural reinvention of the systems that it champions, but a deconstruction and reassembly that has allowed for a deeper introspection of its own mechanics. There’s a tremendous amount of praise to be had for the way in which the game operates, especially when it exists in a climate that treats player engagement like a binary metric rather than a consequence of successful game design. The modern open-world is cynical, and often entirely forgettable. But Death Stranding is unique in the way that it proudly defies the cynicism of its own systems, resisting the pitfalls of the genres that it orbits. In the way that you move, the way that you leave an imprint upon the land and the way that your journey is woven together with that of other players, Death Stranding is a triumph of originality. The realm to which I belonged had little order to it, but throughout its scaffolded valleys and upon its broken roads, I found a place within a community that shared in the belief of moving forward. And when there’s such strength in those connections, no words are ever necessary. Well, apart from “Keep on keeping on”, perhaps.